HISTORY CHATEAU

Building development, owners and landscape

First written record

The region around Vranov in southern Moravia, traversed by the life-giving Dyje river, had invited settlers from prehistoric times. By the 11th century at the latest, i.e. after Moravia had been invaded by Prince Oldřich, a border fortress was built here as part of the defence system along the Dyje river. The first recorded reference to it dates from 1100, and appears in the famous Chronica Boemorum by Cosmas, Dean of the Prague chapter.

The region around Vranov in southern Moravia, traversed by the life-giving Dyje river, had invited settlers from prehistoric times. By the 11th century at the latest, i.e. after Moravia had been invaded by Prince Oldřich, a border fortress was built here as part of the defence system along the Dyje river. The first recorded reference to it dates from 1100, and appears in the famous Chronica Boemorum by Cosmas, Dean of the Prague chapter.

Another record has been preserved from 1323, and refers to King John of Luxembourg exchanging his Vranov estate, including the neighbouring towns, mills, fishponds, forests and other goods, with Jindřich of Lipá, a respected leader of the opposition among the nobility and one of the most influential men in the Kingdom. The wealthy feudal Lichtenburg family, an ancient one with "ostrev" in its coat-of-arms and with large estates throughout Moravia, was yet another significant owner. They had gradually reconstructed, among others, the significant Bítov and Cornštejn castles in the Dyje river basin, and also Vranov, released to them to free hereditary tenancy by the King Vladislav of Jagiello in 1499.

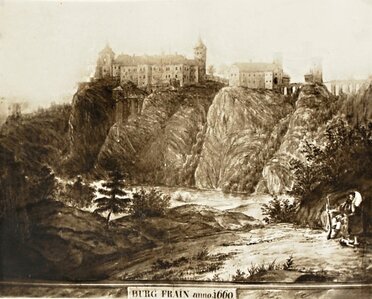

By that time the Vranov valley had already been under the control of a fortified Gothic castle which made prefect use of the natural advantages provided by the elevated terrain and the meandering river. It was erected on the easternmost end of a narrow rock promontory where a one-storey tower with chapel, and a residential palace for the owner, projected towards the bluff, had been built where the ancestors' hall stands today. Access to this part was protected by a massive, cylindrical tower serving most probably as refuge, from where the inner defence could be supported by direct and side fire. The sophisticated fortifications, evidence of which are the existing curtain an enceinte, terminated with the Crow's Tower (Vraní věž), attest to the defensive capacity of the south which was militarily the most vulnerable. The front of the castle, where a medieval, 15th century hot-air heating system has been preserved, was defended from the west by a massive horseshoe-shaped barbican, a prismatic watchtower and fortification walls.

By that time the Vranov valley had already been under the control of a fortified Gothic castle which made prefect use of the natural advantages provided by the elevated terrain and the meandering river. It was erected on the easternmost end of a narrow rock promontory where a one-storey tower with chapel, and a residential palace for the owner, projected towards the bluff, had been built where the ancestors' hall stands today. Access to this part was protected by a massive, cylindrical tower serving most probably as refuge, from where the inner defence could be supported by direct and side fire. The sophisticated fortifications, evidence of which are the existing curtain an enceinte, terminated with the Crow's Tower (Vraní věž), attest to the defensive capacity of the south which was militarily the most vulnerable. The front of the castle, where a medieval, 15th century hot-air heating system has been preserved, was defended from the west by a massive horseshoe-shaped barbican, a prismatic watchtower and fortification walls.

In the 16th century, Vranov frequently changed hands, which only reflected general historic developments. In 1516, the Lichtenburgs were succeeded by the supreme Moravian administrator Arkleb of Boskovice. Other significant owners included Renaissance magnate Jan of Pernštejn, the influential Moravian Lord Zdeněk Meziříčský of Lomnice, and the supreme Prague burgrave Volf Krajíř of Krajk (or Kreig). The aunt of the later Moravian governor Cardinal František, Estera of Dietrichstein who, in the 1580s, had reconstructed the front castle and founded the iron ore mines and iron-mills here with several furnaces, was yet another remarkable figure in Vranov's history.

In the 16th century, Vranov frequently changed hands, which only reflected general historic developments. In 1516, the Lichtenburgs were succeeded by the supreme Moravian administrator Arkleb of Boskovice. Other significant owners included Renaissance magnate Jan of Pernštejn, the influential Moravian Lord Zdeněk Meziříčský of Lomnice, and the supreme Prague burgrave Volf Krajíř of Krajk (or Kreig). The aunt of the later Moravian governor Cardinal František, Estera of Dietrichstein who, in the 1580s, had reconstructed the front castle and founded the iron ore mines and iron-mills here with several furnaces, was yet another remarkable figure in Vranov's history.

Arguably the most significant owner of Vranov was the ancient Althann family, originally from Bavaria, who arrived in Moravia in the last quarter of the 16th century. The ethnically mixed estate of Vranov and Nový Hrádek with four small towns, ten villages and over four hundred families of serfs was first acquired in 1614 by Wolf Dietrich of Althann. However, it was confiscated from him for his participation in the Moravian Estates rebellion in 1619.

The Thirty Years’ War and its aftermath (1629 to 1680)

Shortly after 1629, the estate was purchased by Wallenstein's favourite, general Johann Ernst of Scherfenberg, under whose rule the estate experienced the horrors of the Thirty Year's War. In 1645, after the battle of Jankov, the town of Vranov was invaded and looted by the Swedish army, and the castle was besieged, in vain. After several months' efforts including an attempt at diverting the Dyje river away from the water towers thus "thirsting out" the garrison, the Swedes gave up and, threatened by imperial reinforcements, decided to leave Vranov.

Shortly after 1629, the estate was purchased by Wallenstein's favourite, general Johann Ernst of Scherfenberg, under whose rule the estate experienced the horrors of the Thirty Year's War. In 1645, after the battle of Jankov, the town of Vranov was invaded and looted by the Swedish army, and the castle was besieged, in vain. After several months' efforts including an attempt at diverting the Dyje river away from the water towers thus "thirsting out" the garrison, the Swedes gave up and, threatened by imperial reinforcements, decided to leave Vranov.

In 1665, apparently after a devastating fire had swept the castle, the Stahrenberg family acquired the war-worn and partly deserted estate. The Stahrenbergs made the last major changes to the Vranov medieval fortress, simplifying and levelling the northern facades of the residential buildings, thus completing over six centuries of its architectural history, and anticipating the following period of the construction of a new Baroque chateau.

The Althann family and their Baroque chateau (1680 to 1774)

The Althann family and their Baroque chateau (1680 to 1774)

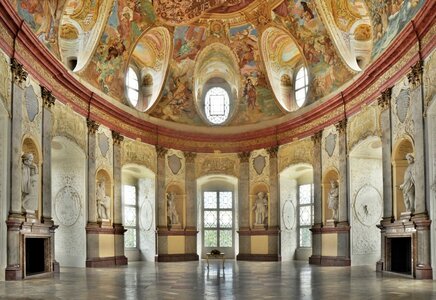

It was started by the ambitious imperial councillor and associate judge at the Moravian provincial court, imperial count Michael Johann II of Althann, who acquired Vranov again for his family in 1680. It was his aim to build a modern, stately aristocratic residence, whose interiors would suit the new requirements of the times. Thanks to a lucky flash of intuition he selected as the chief artist a prominent figure of Central European Baroque, the young Court Architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, the later builder of the Palais Clam-Gallas in Prague, the Karlskirche in Vienna, religious buildings in Salzburg, and the first designer of the imperial residence at Schönbrunn.

Shortly after 1687, the construction of a monumental ancestors' hall started after Fischer's design on an oval ground plan and with a bold cupola. The landmark of the future chateau, overlooking the surrounding landscape and organically blending with it, was decorated by artists like the Viennese sculptor Tobias Kracker, who put sculptures of prominent members of the family of Althann in the niches along its perimeter, inventive Italian masters who added stucco ornaments, and above all Johann Michael Rottmayr, who painted the grand allegorical mythological fresco in the cupola. In the course of eight years (1687-1695), one of the gems of secular Baroque architecture was created, of a remarkably balanced composition, whose individual components are in perfect harmony and serve one aim, namely to celebrate, with due pride, the family of Althann, its antiquity, its merits both real and fictitious, and its dynastic thinking.

Shortly after the completion of the hall, the art-loving count Michael Johann II organised yet another project by the genius that was Fischer von Erlach, asking him to build the chapel of the Holy Trinity with the Althann family vault in the basement. In a mere two years (1699 and 1700), a fine new structure was erected in the free space on the promontory, consisting of a central cylindrical nave with six oval rooms symmetrically placed along its perimeter. It was decorated by the Austrian Ignaz Heinitz of Heinzenthal who added to the oval panels above the altars paintings on themes like Heaven, Paradise and Last Judgement, with the fresco in the cupola depicting the family patron and protector of the church, Archangel Michael. The chapel, a counterbalance in terms of both idea and composition, to the ancestors' hall, and with its iconography reminding of the transience of being, man's last affairs and his permanence in eternity, is again linked with the family idea, celebrating the Althanns.

Michael Johann II died in 1702. His ideas were then carried out by his firstborn son Michael Hermann and, after 1722, his daughter-in-law Marie Anne Pignatelli, a charming and intelligent favourite of the Emperor Charles VI. She asked - most probably Court Architect Anton Erhard Martinelli - to build a three-wing extension, and had the access bridge, parts of the front castle, facades, and the interior of the chapel, reconstructed. Under her, the two-flight Baroque staircase of the great courtyard was decorated with two sculptures. The dynamic, ingeniously composed sculptures, made most probably by the Italian master Lorenzo Mattielli, depict Herakles fighting with Antaeus, and the Vergil-glorified Aeneas saving his father Anchises from burning Troy. They are a personal gift from the Emperor to the cultivated "Marianne" who wielded an influence on the monarch, and who was his host at Vranov on several occasions.

Her son, General Michael Anton Althann, contributes to the completion of the Baroque chateau with only minor adjustments; he rather concentrates on erecting ecclesiastical buildings in the townships and villages within the Vranov domain and on the extension of the manorial woods and their more effective utilisation for hunting deer.

Classicist conversion of interiors and establishment of a forest park (1774 to 1799)

Yet another important chapter in the history of the chateau's architecture began at the close of the 18th century when (in 1774) the estate was inherited by Michael Joseph, the last member of the Althann family at Vranov. He concentrated on having quickly decorated the interiors of the first floor with fine stucco, wall paper and wall paintings oscillating between Late Baroque and Romantic style, under a strong influence of the emerging Classicism. These decorations have been preserved to this date. He also had the garden adjacent to the ancestors' hall newly landscaped as a terraced one and decorated with antique-inspired triumphal arches with the busts of Socrates and Pallas Athena.

Classicism, however, influenced not only the chateau itself but also its immediate surroundings. The Bohemian lawyer Joseph Hilgartner of Lilienborn, who acquired the estate in 1793 in bankruptcy proceedings, linked up with what the last member of the Althann family had started, and focused on completing the landscaping of the park. A look at the authentic design of 200 years ago, bearing signs of a pre-Romantic, Rousseau-inspired relation to nature, very well documents the period lifestyle as well as Lilienborn's intentions - a rugged, irregularly forested ground is criss-crossed by paths and brooks, dotted with arbours, an antique temple, artificial caves, stone benches and little gardens decorated with sculptures, and complete with a lake and waterfall, all inviting to rest. The very active and imaginative owner, ennobled shortly after he acquired Vranov, also reconstructed the pheasantry and the game reserve with a summer hunting lodge, as well as the stable and carriage shed at the entrance to the chateau, founded new villages and constructed new roads.

Classicism, however, influenced not only the chateau itself but also its immediate surroundings. The Bohemian lawyer Joseph Hilgartner of Lilienborn, who acquired the estate in 1793 in bankruptcy proceedings, linked up with what the last member of the Althann family had started, and focused on completing the landscaping of the park. A look at the authentic design of 200 years ago, bearing signs of a pre-Romantic, Rousseau-inspired relation to nature, very well documents the period lifestyle as well as Lilienborn's intentions - a rugged, irregularly forested ground is criss-crossed by paths and brooks, dotted with arbours, an antique temple, artificial caves, stone benches and little gardens decorated with sculptures, and complete with a lake and waterfall, all inviting to rest. The very active and imaginative owner, ennobled shortly after he acquired Vranov, also reconstructed the pheasantry and the game reserve with a summer hunting lodge, as well as the stable and carriage shed at the entrance to the chateau, founded new villages and constructed new roads.

Polish traces (1799 to 1939)

The 19th century, when the chateau was in the hands of the Polish aristocratic family of Mniszek and, from 1876, of the related family of Stadnicky, brought no major changes to its architecture. The most remarkable 19th-century additions are probably the wall paintings in the interiors of the western wing (from the time shortly after 1800), made apparently at the request of the young Count Stanislaw Mniszekand inspired by "spiritual alchemy", or a timeless, mystical philosophy of life, undescribable by conventional science. Likewise, the monumental, French Imperial style extension to the faćades of the stables and carriage sheds, the minor neo-Gothic and Romantic changes of the faćades elsewhere, and the efforts of both families dedicated to the cultivation of the chateau park and the chateau's environs, with chapels, crosses, obelisks, and family memorials erected here and there, and great attention devoted also to the forests.

The 19th century, when the chateau was in the hands of the Polish aristocratic family of Mniszek and, from 1876, of the related family of Stadnicky, brought no major changes to its architecture. The most remarkable 19th-century additions are probably the wall paintings in the interiors of the western wing (from the time shortly after 1800), made apparently at the request of the young Count Stanislaw Mniszekand inspired by "spiritual alchemy", or a timeless, mystical philosophy of life, undescribable by conventional science. Likewise, the monumental, French Imperial style extension to the faćades of the stables and carriage sheds, the minor neo-Gothic and Romantic changes of the faćades elsewhere, and the efforts of both families dedicated to the cultivation of the chateau park and the chateau's environs, with chapels, crosses, obelisks, and family memorials erected here and there, and great attention devoted also to the forests.

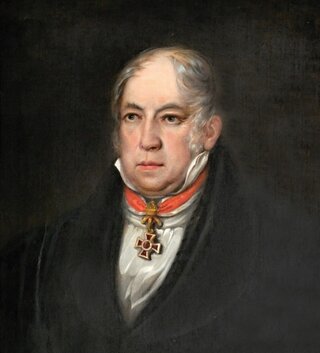

The owners of the estate, however, also cared about the economic prosperity of the surrounding region. In 1816, the skilful organiser Stanislaw Mniszek purchased a rather insignificant earthenware factory in Vranov to make of it a large, prosperous one which made a major contribution to the development of pottery production in the Czech Lands.

The main contribution of the Mniszeks and Stadnickys was also the exceptionally rich culture, though mainly oriented on France. They established and constantly enlarged the big library, the books in which document the fine literary tastes of the chateau owners. Theatre was played directly at the chateau, the Mniszeks themselves were fine musicians and good composers, played chamber music, and invited renowned artists, composers, and actors from Viennese theatres to Vranov either to perform, or to stay for a couple of days. The cultural atmosphere of the Vranov chateau was particularly preferred by some famous writers, e.g. the Nobel Prize winner Henryk Sienkiewicz.

In 1938, when Vranov became a part of Hitler's Reich, the chateau and the estate were confiscated from Adam Zbygniew Leo Stadnicky and sold to the German Baron Gebhard von der Wense-Mörse. After World War II, the state became the new owner of the property and made the national heritage site accessible to the public.

In the 1970s, a large-scale reconstruction was undertaken of the networks, roofs, faćades and fortifications. First floor "piano nobile" interiors were refurbished, more rooms were opened to public access, and the movables were restored. A new ticket office and a new historic exposition at the entrance were added, while the surrounding park also underwent large-scale restoration.

The tour of the chateau now includes the ancestors' hall, the chapel and other interiors, offering an insight into life at the chateau at the end of the 18th and through the 19th centuries. The original products of the Vranov earthenware factory are given a prominent place. The chateau as a living thing of its own character, created and gradually moulded by people and historic tradition is not an isolated artefact. Placed in an organic context, it is also remarkable for its natural environment which is a part of the strictly protected Podyjí National Park. A fragment of the original landscaped forest with the surviving structures, and the authentic free landscape around it have an immense aesthetic, and emotional, value, also thanks to the wealth of the flora and fauna, and the geological rarities.

The combination of the river Dyje, the rocks, forests, the bold structure of the chateau as well as the deep skies above it command our respect as a clean, pure, character being, uniting in itself the force of the Earth and the ideas and skill of Man. At the same time, one can clearly feel, in the rhythmical rush of restlessly flowing time, the arcanum of the place, its bewitching genius, telling with unprecedented power that all living things, everything that exists, is a single organism given an illusive form. We feel the need - in the face of the urgent risks of the time - to strive for a more profound knowledge and understanding of the cosmic order and the role of Man within it, in one's own interest and in the interest of restoring unity with the Universe.